Mixed reality headsets enhancing surgical precision at Prince of Wales Hospital

)

The Hong Kong-based hospital is believed to be the world’s first to systematically develop and apply Mixed Reality (MR) in orthopaedic oncology – offering surgeons ‘X-ray vision’ beneath the skin for precision surgery

For orthopaedic oncology surgeons – specialists who remove tumours from bones and soft tissue – there is immense pressure in making ‘a good cut’: one that removes the tumour entirely, but no more than necessary. A cut that removes too much normal bone and tissue compromises a patient’s function, but a cut that doesn’t completely remove tumour cells risks the tumour recurring.

Making this right cut wasn’t easy in the past. Surgeons only had 2D images, in the form of CT or MRI scans, to plan surgeries. In areas with complex anatomy, like the pelvis or abdomen, visualising the surgery can be difficult, leading to suboptimal surgery outcomes.

The advent of 3D printing technology in the 2010s changed that. At Hong Kong’s Prince of Wales Hospital (PWH), an in-house surgical planning and 3D printing lab was established in 2021 that creates patient-specific surgical guides and instruments for precise tumour removal.

“Now, by using the patient’s scan images to print a physical 3D bone tumour model and the patient-specific instruments needed to remove it, we take just 10 minutes. Our study also showed that this method is very accurate, with an error margin of less than 2mm.”

Nonetheless, though the hospital’s use of 3D printing has taken off – around 300 models are printed each year – there are limitations to the technology.

|

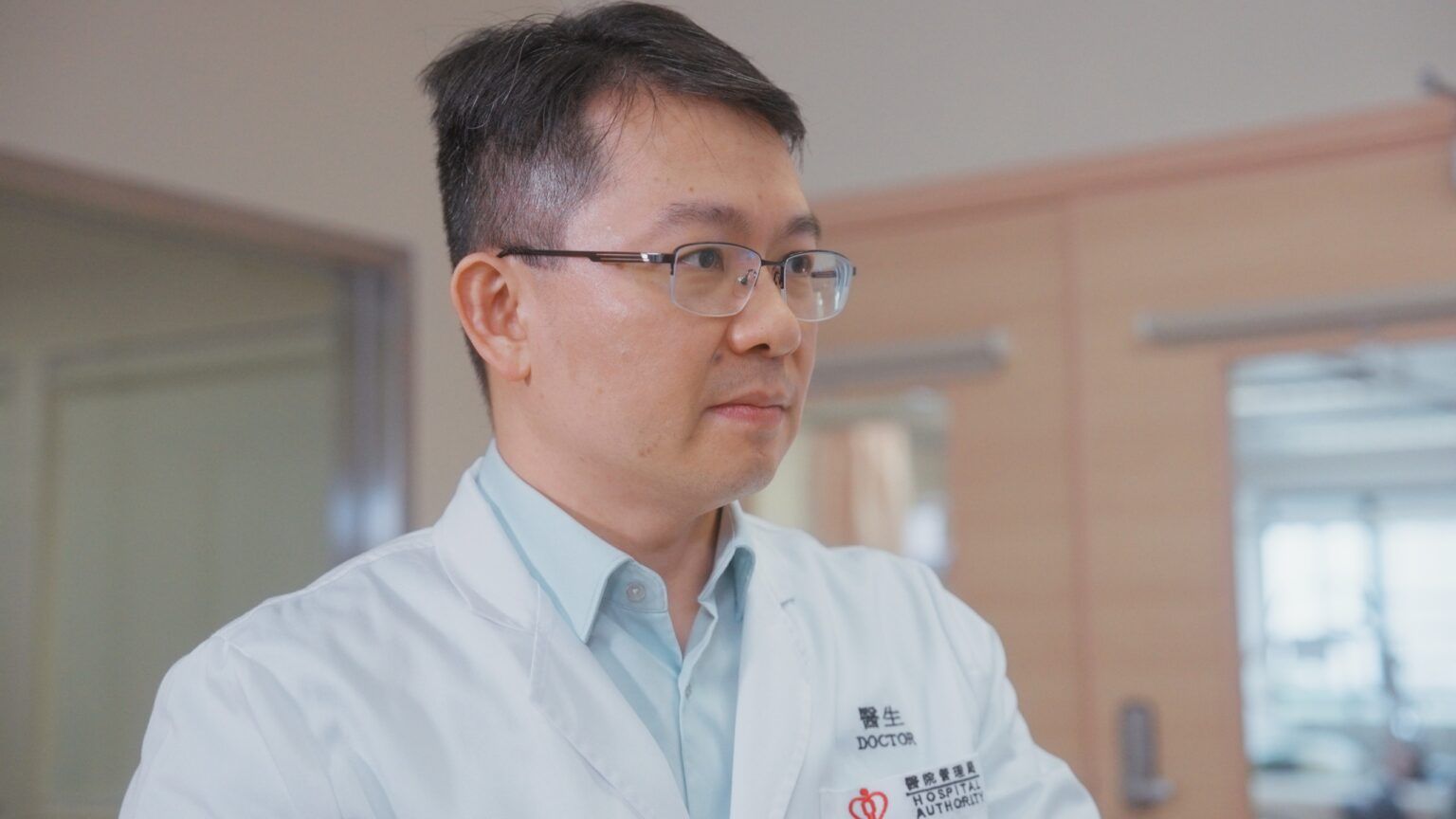

“In the past, we may take around 30 to 45 minutes guessing where to make the cut, or ordering repeated X-rays just to make sure,” said Dr Wong Kwok-chuen, Consultant at PWH’s Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, and Clinical Lead of the 3D Printing Office. |

For one, 3D printing can be time and resource intensive, with multiple processing steps. While some surgeons may prefer having multiple models depicting different parts of the body anatomy, such as the tumours, muscles, vessels, it is not feasible to do so for every surgery case.

The rise of mixed reality technology in surgery

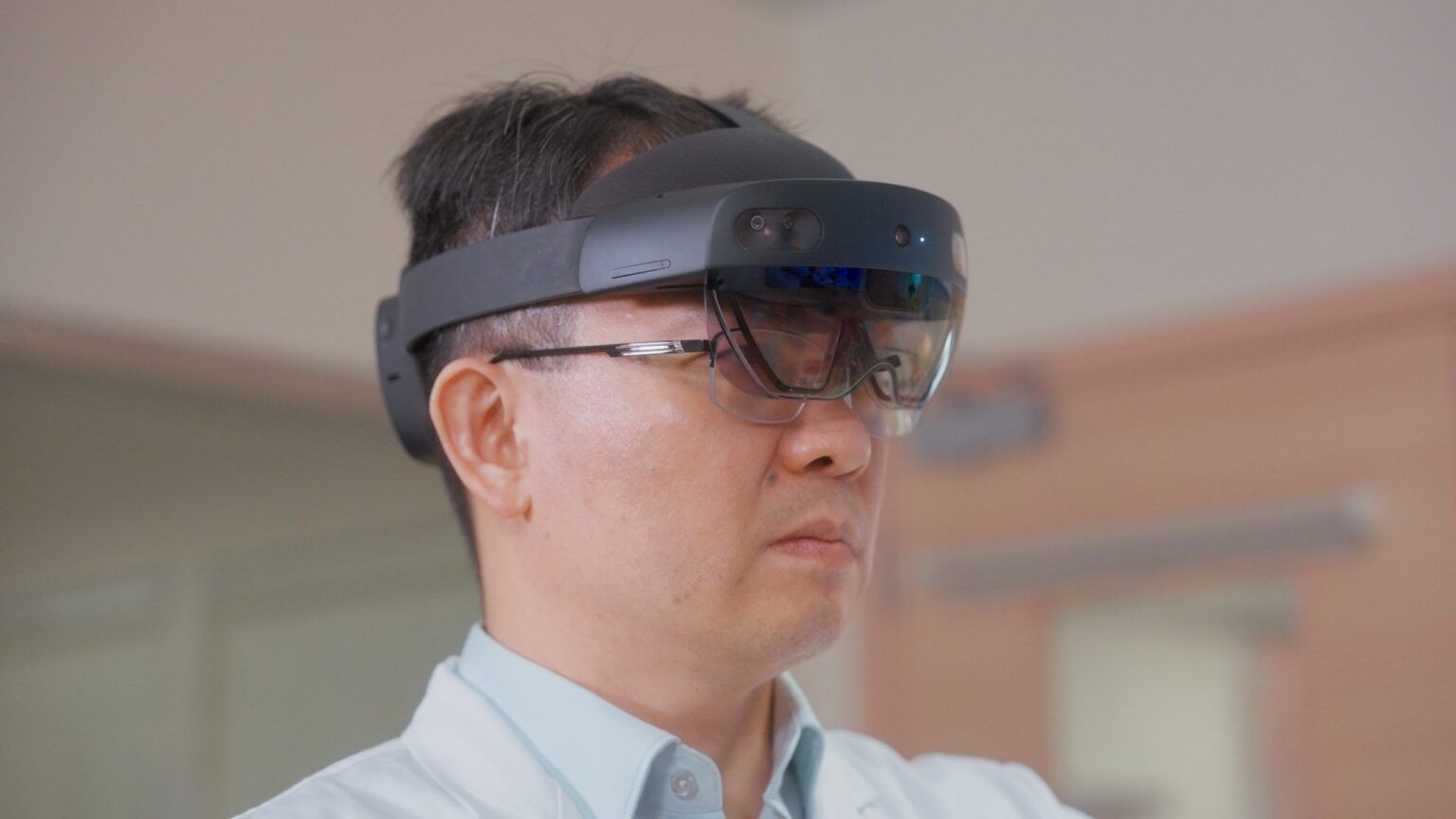

Seeking a more accessible solution, the team turned to mixed reality (MR) technology, which overlays digital information onto real-world objects and allows users to interact with it.

“When we put on the MR headsets and see a virtual overlay of the patient’s scans, we gain something like X-ray vision: We can look beneath the skin to see the muscle, bone, tumour, and other structures. It is much more intuitive for the surgeon, who no longer needs to mentally translate a 2D image or 3D printed models,” said Dr Wong.

Over the past three years, PWH has utilised MR headsets in 65 bone and soft tissue tumour surgeries, with zero complications and positive feedback from surgeons on improved surgery precision and efficiency. The hospital is believed to be the only one globally leveraging MR routinely in orthopaedic oncology at the moment.

The use of MR in this context comes with very low risks, Dr Wong pointed out.

“We mainly use MR headsets to get the operative view before making any skin incisions. In this sense, MR technology simply offers us a new and intuitive way to look at the image directly on the patient’s body.”

Moreover, these headsets also offer valuable applications in clinical collaborations.

“In the operating theatre, the surgeon is often quite alone – it is difficult to consult with colleagues on surgical decisions. With the MR headsets, surgeons can share a first-person view of the surgery with their colleagues, even those overseas, for real-time discussion. Junior surgeons can also put on the headsets for a more interactive learning experience.”

The success of MR in the hospital setting hinges on seamless access to the facility’s data network.

Building up the data infrastructure was relatively time-consuming – taking almost a year – but crucial for surgeon adoption. Surgeons are unlikely to use the headsets if they needed to manually load patient data before each procedure, Dr Wong pointed out.

Today, surgeons can request a mixed reality case assessment for their patient directly through the hospital Clinical Management System. The request is directed to the 3D printing office, which generates the MR model and uploads it to the hospital server.

The goal is to make the process as fuss-free as possible – surgeons simply download the patient’s digital model to the headset when they are in the operating room, and they are all set.

Envisioning the future: AI-driven MR devices

With the hardware and software infrastructure now in place, PWH plans to scale up the use of MR technology across more surgical disciplines, including urological surgery, cardiothoracic surgery, plastic surgery and ENT, which typically rely heavily on CT and MRI images.

The 3D printing office will support new users by directing their access and onboarding.

Meanwhile, the office is also running two research and development projects around the potential of MR in clinical practice.

The first focuses on improving the MR software used in orthopaedic oncology surgery, so the digital models track the movement of the bones and move accordingly.

The other delves into the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into MR headsets, so surgeons have access to real-time guidance, such as viewing specific surgical steps or instrument recommendations.

This combination of AI and MR may not be far off – after discussions with the engineering team, Dr Wong believes MR devices with AI virtual surgical assistants can be expected within the next five years.

Ultimately, these rapid developments in clinical technology will only benefit surgeons and patients, Dr Wong emphasised.

“There are many different factors that affect the outcome of surgical procedures. What we are doing now is leveraging technology to improve those factors that we can control, such as by better understanding of patient anatomy.

“The next phase of development around AI-assisted MR will help to further support surgeons. They may be physically alone in the operating room, but they will be virtually assisted with the latest medical information, real-time data, and their peers. All these translate into more accurate and precise surgery, and better surgical outcomes for patients.”